Mitochondria: Introduction to Cell Communication

Learning Objectives

- Understand the Structure and Function of Mitochondria

- Mitochondria and Cellular Signaling

- Mitochondrial Dysfunctions and Disease

- Cell Communication

Mitochondria

Small organelles in eukaryotic cells often referred to as the “powerhouse of the cell.” They generate ATP through oxidative phosphorylation, contain their own DNA, and are believed to have originated from endosymbiotic bacteria.

Structure

- Outer Membrane: A simple phospholipid bilayer containing large integral proteins called porins. It allows the passage of ions, nutrient molecules, ATP, ADP, etc., with ease.

- Inner Membrane: Freely permeable only to oxygen, CO2, and H2O. It contains proteins for oxidative phosphorylation, ATP synthase, transport proteins, and machinery for mitochondrial fusion and fission.

- Intermembrane Space: Known as the perimitochondrial space, it has a high proton concentration.

- Matrix: Enclosed by the inner membrane, this space contains enzymes, mitochondrial DNA, ribosomes, tRNA, and other components.

- Cristae: Folds of the inner membrane that increase surface area, enhancing ATP production.

Functions of Mitochondria

Primary Role: Production of ATP through cellular respiration.

Other Functions:

- Regulation of metabolic pathways

- Calcium signaling

- Apoptosis (programmed cell death)

- Heat production (thermogenesis)

Introduction to Cell Communication

Cell communication is the process by which cells detect and respond to signals in their environment. It involves chemical signals like hormones, neurotransmitters, and other molecules.

This process is crucial for maintaining homeostasis, coordinating cell activities, and responding to external stimuli.

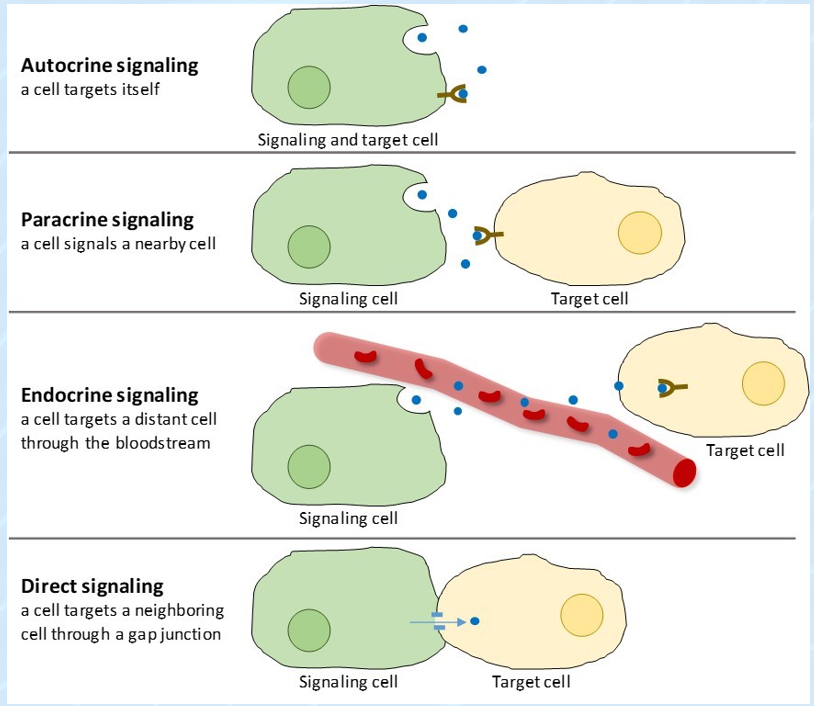

Forms of Signaling

- Autocrine signaling

- Paracrine signaling

- Endocrine signaling

- Direct contact

Mitochondria and Cell Signaling

Mitochondria play a key role in regulating important cell signaling pathways, including:

- Calcium Signaling: Mitochondria act as calcium buffers, regulating intracellular calcium levels and preventing calcium overload.

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Signaling: ROS are byproducts of mitochondrial activity. Low levels act as signaling molecules, but excessive ROS cause oxidative stress, leading to cellular damage.

- Apoptosis: Mitochondria are critical in initiating programmed cell death, which removes damaged or unwanted cells.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cell Communication

Mitochondrial dysfunction impairs cellular signaling, leading to issues like cell death, uncontrolled growth, or failure to respond to environmental signals. Conditions linked to dysfunction include:

- Neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s)

- Oxidative stress and inflammation

- Calcium overload

Mitochondrial Diseases

- Mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS)

- Leigh syndrome

- Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON)

- Kearns-Sayre syndrome (KSS)

- Myoclonic epilepsy and ragged-red fiber disease (MERRF)

Neurodegenerative Diseases

- In these diseases, abnormal mitochondrial function leads to excessive ROS production and defective ATP generation, contributing to neuron death.

- Impaired mitochondrial dynamics, including fusion and fission processes, exacerbate the disease progression.

Mitochondria in Cancer

- Cancer cells often exhibit altered mitochondrial function, promoting aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) even in the presence of oxygen.

- Mitochondria support cancer cell survival and proliferation by controlling ROS levels, promoting resistance to apoptosis, and contributing to tumor metastasis.

- Targeting mitochondrial function is a promising strategy in cancer therapy.

Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and other conditions by promoting oxidative damage and affecting ATP production.